This article looks at how science fiction storytelling can be used as a technique in gaming. Specifically, we look at how plot prompts can be used alongside characters and situations to help players intuitively craft stories in storytelling games like Peek. Then, we go ahead and tell a few stories using cards from the game to demonstrate the mechanic in action.

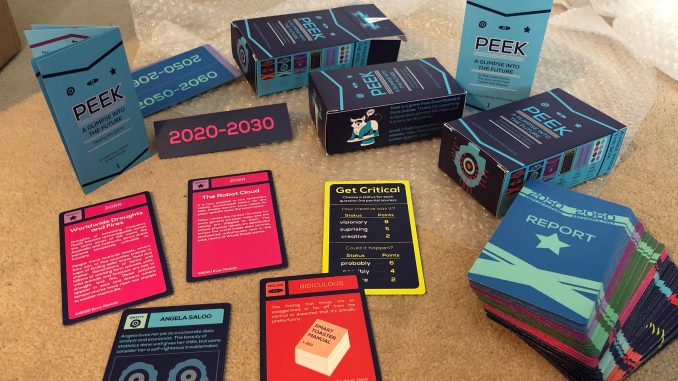

About Peek

Peek is a game that allows people to look into the future. It provides a glimpse of a world shaped by people, entities, events, facts and feelings. Using these storytelling elements, they report back to the group about their visions of the future. The skill in playing the game is to make reports both convincing and also creative.

The game is a response to the disinformation prevalent in popular media, and in particular the difficulty in explaining AI and machine learning and their benefits and drawbacks to lay audiences. For example, as well as the obvious issue of automation taking human jobs, the precarious sustainability of large banks of power-hungry computers running AIs is a theme in the game. There is a real need to educate people about how these potentially disruptive technologies could transform society, one way or another.

Our world is now science fiction

As theorist Dan Hassler-Forest (2019) pointed out, science fiction is now transmedia: it takes place across different almost all forms of media, from comics to games to television to social media. As Star Wars creator George Lucas lucratively discovered, science fiction movies can expand into a larger world of books, toys, comics, card games, games — almost any form of media into which a character can be illustrated, or sculpted out of.

Science fiction novels can take place across time as well – Ingrid Burrington and Brendan C. Byrne’s “The Training Commission” (Burrington and Byrne 2019) explored a number of science fiction concepts through an email newsletter at irregular intervals and links to the distributed web. Given the perceived strangeness and dystopian feel of current times where formerly stable democracies have exposed the innermost thoughts of unhinged leaders online, a global pandemic has locked many of us into our homes and daily occurrence like online “armies” of Korean pop star fans battling American police organisations through social media attacks, a number of people feel like everything has become science fiction.

Science fiction, it could be argued, has become a frame of reference for dealing with the ways that digital technologies are accelerating changes in our world. A search for the phrase “This is the longest episode of Black Mirror” (referencing the popular and darkly humorous science fiction show “Black Mirror” originated by Charlie Brooker) turns up a number of tweets dating back to 2016.

In Russia, it is alleged that President Putin’s advisor Vladislav Surkov secretly writes dystopian science fiction stories about non-linear war as a potential exercise in battle strategising (Komska, 2014). If so, he would be in good company as it is no secret that the United States used “scenario planning” in the 1950’s where Hollywood screenwriters were drafted into science fiction war-gaming exercises to help oppose the Soviet Union in the Cold War (Kleiner, 2003). Twentieth Century governments have long understood that “a critical… reading of science fiction is essential training for anyone wishing to look more than ten years ahead” (Clarke, 1963).

Game mechanics for storytelling

Storytelling, like any form of art, has with some basic tools of the trade. In Christopher Booker (2005)’s view, there are only seven fundamental storylines that can be worked with or against and combined in different ways. His work built on Joseph Campbell’s popular concept of the monomyth (Campbell 2008), and its concept of a story cycle following a main character called the “hero” on their journey through a series of challenges. Dan Harmon’s adaptation, which helps shape the plots of the popular science fiction cartoon Rick and Morty, was particularly influential in our work (Harmon 2013).

Stories have characters and settings. Interestingly, Charles Yu’s 2011 novel “How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe” describes pseudo-scientific theorem linking “science fiction universes” with imaginary physics and the resulting narrative trajectories and typologies of characters to be found in them.

Whilst we didn’t come up with a unified equation for characters and situations, we did put together a basic formula that worked well in our tests: Entity + Feeling + Reports.

- Entity: a person, organisation or thing

- Feeling: a prompt that helps relate the narrative to one of the seven basic plots from Booker

- Reports: mini-stories that fit on a card and provide background and inspiration

Scoring stories

Games often use the mechanic of collecting “points” to motivate players to do something, or to help decide a “winner”. In Peek, you can win the game if you use the most game cards in your stories and also tell the best stories, as decided by your critically-sophisticated fellow players.

Each of the players in Peek starts in a specific future time period (e.g. 2020-2030 or 2040-2050) with an Entity (main character), a Feeling, and a few Reports. The mechanism is that each player takes turns telling short “facts” about their character and time period. After trading a few facts with one another, a common story-world starts to emerge that includes cards from other players and riffs on each others’ ideas.

Then, players take turns telling a short story about their Entity (main character), starting in their time period and ending… wherever and whenever! The other players listen to this story and then try to be critical about how creative (and entertaining) it was, and also how plausible it seemed (so stories don’t become too unhinged from reality).

They assign points based on a special “Get Critical” card:

Players also get points for using other people’s cards in their story, as do the “owners” of those cards. This keeps the game collaborative, to reward players who created interesting facts about their cards that were irresistible not to use in other stories.

Telling stories

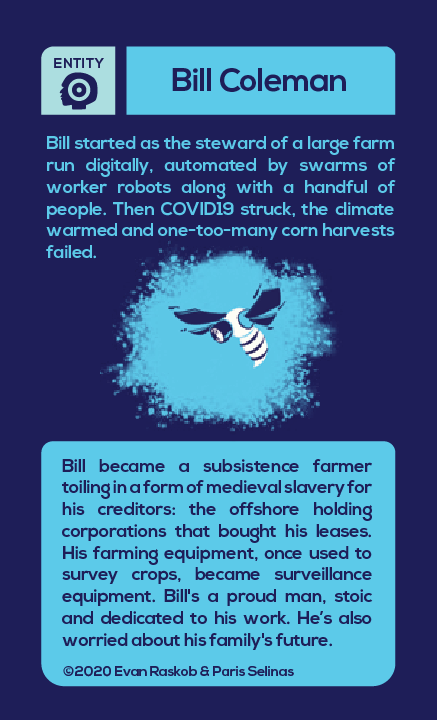

Let’s demonstrate how intuitive it can be to create stories from the cards. The following are cards from actual Peek player hands: an Entity (character) card and a Feeling (plot) card. For each hand, I will discuss the backstory of each card and occasionally invent a few “future facts” about them and explain how they might lead to a short story.

|  |

About the cards

Shada Ali is an attempt to get more women of colour into the game, especially strong ones like the real artist she is informed by. I’m hoping to get more diverse writers involved in future versions of the game. What’s interesting about this card combination is that Unnatural is partially a reference to the classic “Hero’s Journey“ plot, where a “hero” character goes on a journey to slay a threatening and legendary beast. In this case, there is a duality to the combination, where you can imagine that some conservative thinkers could consider Shada’s provocative art work to be a blasphemous abomination that must be destroyed, whereas she might feel that powerful members of society with their misinterpretations of religious texts are against the way things should have been.

|  |

About the cards

We all know someone like Will, someone a bit off who thinks everything is everyone else’s fault. Strangely, we live in a time where anyone can get up on a YouTube soapbox and discover their hidden charisma and gain a cult following. I thought up this card while listening to Rabbit Hole, a podcast from the New York Times that looked at the polarised cultures forming amongst YouTube binge-watchers. Even Will might get his day, on YouTube, if he can get a green screen for his AutoTruck so people don’t have to keep staring at the empty McDonalds wrappers piled up in the background of his videos.

Rags to riches — 2040-2050

|  |

About the cards

“Pluck” was a really difficult card to create and one of the harder cards to use in a story, for some reason. It represents the classic “rags-to-riches” story line of plucky orphans who find themselves adopted by the ultra-wealthy or otherwise improbably successful as in the classic musical Annie or English story Dick Whittington and His Cat. Success brings peril, however.

This plot is something like a journey, but starting from tragic circumstances that can only be resolved by luck. It is related to a quest or a journey, in which a central character has to overcome a series of difficulties to achieve greatness.

A quick story

- Bill and his family are currently hapless prisoners in their own panopticon created out of the sensors in his farming equipment, now owned by an off-shore corporation partially owned by British ex-Prime Minister David Cameron. He can’t afford to meet the monthly payments on the equipment leases, so until he can raise the funds the machines have started autonomously farming his plot of land and using the proceeds to pay for their basic upkeep (gas, maintenance, electricity).

- One day, Bill and his wife realise that they don’t have enough to last through the next two months. They decide to send Bill to the nearest city, Birmingham (UK) to see if he can get some work and start paying down the debt they owe and taking back control over some of the machines. Bill wanders the streets for days, sleeping rough until he finds a little circuitboard wedged into a stone wall in a park. It has a BitCoin icon on it, and appears intact.

- Bill hurries to an Internet Cafe (yes they still exist) and plugs in the little device. He finds £1M in BitCoin on the device, and before he can do anything else a window pops up that says “Installing…” and some rogue software takes over the computer. Another window appears with a video of David Cameron, now in his 70’s. David explains that he has planted this wallet in a place where he hoped someone destitute would find it, as penance for his disastrous handling of the Brexit referendum so many years ago. He also leaves instructions on how to meet him at his city home so he knows his gift has been found.

- Bill quickly transfers the BitCoin into his personal account and emails his wife. He downloads a little credit to his phone so he can take a train across town to meet Cameron. About an hour and a half later he is standing in front of the suburban home of Cameron, the man who, unbeknownst to him, is the majority owner of the equipment that has imprisoned him and his family for years.

- David greets him with a smile and a shake of the hand. He proves to be a gracious and generous host, explaining that his wife has left him a few years back and his health is now poor, despite the genetic reprogramming treatments. In his precious time left, all he would like to do is right a few wrongs and make peace with the world before he leaves it.

- Bill is surprised when another man enters the room and asks if everything is alright. “My lawyer,” says David. He explains that he has some pressing paperwork to attend to and offers Bill a room for the night before his long trip home to his family and farm. On the way upstairs to the guest quarters, the lawyer gives Bill a fierce look before quickly turning back to Cameron.

- In the morning, Bill wanders downstairs to find breakfast on the table and a note from Cameron apologising for having to leave, but offering Bill the use of his private helicopter and pilot to return home swiftly and safely. Bill is back in his old home, his head spinning, his wife leaping for joy, a rich man but also unsettled somehow. Back in the house he’d noticed the Cameron coat of arms looked very similar to the logo on the statements of the farming equipment lease-holders. Similar, but not exact. Coincidence?

The scoring

I told this short story to my partner. She gives it a “surprising” because “it’s not quite visionary but was definitely surprising” and “probably” because “the characters could act like that, and people have chance encounters like that. Like something you’d watch in a movie.” Final score: 9 points.

This article was originally published by Evan on Notion

References and further reading

Booker, Christopher. The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. London: Bloomsbury. 2005.

Burrington, Ingrid and Byrne, Brendan C. The Training Commission. 2019. Online: http://trainingcommission.com/

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 3rd ed. Novato, Calif.: New World Library. 2008.

Davis, Meredith. “Introduction to Design Futures.” AIGA. Online: https://www.aiga.org/aiga-design-futures/introduction-to-design-futures/ (Retrieved May 31, 2020)

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. Speculative Everything Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. 2013.

Harmon, D. Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit. 2013. Online: https://channel101.fandom.com/wiki/Story_Structure_101:_Super_Basic_Shit (Retrieved June 1, 2020)

Hassler-Forest, Dan. Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Politics: Transmedia World-Building Beyond Capitalism. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Kleiner, Art. The Man Who Saw the Future. Strategy+Business, Issue 30. (Feb. 12, 2003). Online: https://www.strategy-business.com/article/8220?gko=0d07f

Komska, Y. “Can the Kremlin’s bizarre sci-fi stories tell us what Russia really wants?” Pacific Standard. (April 15, 2014) Accessed June 1, 2020. Online: https://psmag.com/social-justice/can-kremlins-bizarre-sci-fi-stories-tell-us-russia-really-wants-78908

Pomerantsev, P. “The hidden author of Putinism.” The Atlantic. (November 7, 2014). Online: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/11/hidden-author-putinism-russia-vladislav-surkov/382489/

Yu, Charles. How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe. London: Corvus, 2011.

Zaidi, Leah. “Worldbuilding in Science Fiction, Foresight and Design.” Journal of Futures Studies, June 2019, 23(4): 15–26

- Sex and the pandemic - 15th March 2021

- The Mechanics of Plots in Peek - 12th March 2021

Be the first to comment