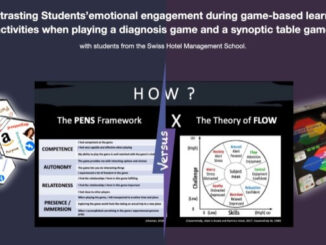

We often hear the term ‘Flow’ being bandied about with reference to the playing of certain games, as well as in learning settings, so it would seem it is an important concept within both of the contexts of games-based learning.

Probably the most well-known theorist / writer on the topic of Flow was Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the Hungarian American Psychologist who died in October 2021. He worked in the fields of Creativity and Happiness and was the author of the book, ‘Flow: the Psychology of Optimal Experience’.

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience is available on Amazon

It is likely that you will hear people referring to ‘flow’ both as a state of optimal concentration on a particular activity, and the experience of being in that state. Those who experience flow describe it as a state of complete absorption, where any external concerns, including time, the needs of the body, and so on, fall away. Many refer to it as being ‘in the zone’, and report feeling very skilled at what they are doing, where one action leads to the next seemingly effortlessly.

Csikszentmihalyi posited that three conditions contribute to the flow state.

The balance between the perception of the challenges of the tasks and perception of one’s ability to perform it. In other words, the task must lie in a perceived ‘Goldilocks Zone’ where it is neither too easy (which would break absorption through boredom) or too difficult (which would bring about the frustration of failure).

Clear goals which help to establish the structure of the activity and to indicate progress

Clear and immediate feedback helps to maintain flow by measuring progress towards goals and allowing swift adjustment to performance.

The first of these is often seen as the most important because, if the perception of challenge is well-designed for, that will necessarily include clear goals and feedback.

In addition to the feeling of absorption and perception of achievement, flow experiences are also characterised by a feeling of being in control and loss of reflective self-awareness.

Flow requires active participation, so passive activities such as watching television will not elicit a flow experience. Given that Csikszentmihalyi believed that flow experiences contributed to overall life satisfaction, this has deep implications in fields like education and learning (passive vs experiential learning methods), and design of workplace activities, both of which Csikszentmihalyi was interested in.

Other researchers have applied his work to other fields including music, sport, games and play and the workplace. It is important to note that beyond the positive feelings experienced by people ‘in flow’, the state is also associated with persistence and high achievement, so it is seen as a beneficial characteristic to design for.

Flow in Learning

The balancing of skills with challenge is consistent with a number of other theories and practices in education and learning. For example, the practice of ‘scaffolding’, where new learning is built on a basis of previous learning is very consistent with keeping a learner in flow as their perception of complexity (of the task) and their own skills can move forward at a similar pace towards a well-defined goal.

Likewise, one of the intentions of ‘differentiation’ is to match learning to the needs and capabilities of learners, which would also serve to maximise the potential for flow-creating situations. This can also be a way to ensure ‘relevance’ to learners which is one of the requirements of the Andragogy theory of Malcolm Knowles – the level at which someone is operating within their n a workplace task, would be an aspect of the relevance of learning to their life/work.

Flow is obviously, within itself, a rewarding state, which learners are motivated to achieve, so designing for flow is an effective way to keep learners engaged in learning. It is often cited as a reason for using games in learning, because well-designed games are engines for flow.

Flow in Games and Play

Games establish clear goals through their winning conditions, as well as smaller sub goals that players must carry out in order to progress within the game.

Well-designed games make is easy for players to understand how well they are doing within the context of the game, and to adjust their actions to play ‘better’, by feeding back on player actions through mechanisms such as scoring or position. For example, when pieces are taken in Chess, a player can see how they are doing in comparison to their opponent by how much ‘material’ they each have remaining. They can also see from the position of the pieces on the board, whether they threaten or are threatened and the capability of different pieces to influence the game.

Through the above, players take part in learning which progressively improves their ability to play. So long as the game is not seen as ‘too difficult’, or ‘too easy’, the matching of perceived ability and challenge will keep the player in flow. This may of course involve matching oneself to opponents who provide the right level of challenge, or applying a ‘handicap’ to level the game for players of differing abilities. The benefits achieved can be self-perpetuating, because the challenges of learning to play can keep the player in flow, meaning they wish to continue to play, meaning they continue to learn.

- James Bore – The Ransomeware Game - 13th February 2024

- Ipsodeckso – Risky Business - 23rd January 2024

- Review – Luma World Games - 15th December 2023

Be the first to comment