Contrasting students’ emotional engagement during game-based learning

This article is adapted from a paper by Xavier Wilain (2022) Contrasting Students’ engagement during game based-learning. Paper presented at the Games and Serious Games Syposium, Geneva on 30 June 2022. Proceedings, p14-17. It has been made available to Ludogogy by M. Wilain.

Abstract

This research aims to measure students’ perception of their emotional engagement in game-based learning activities and compare them in regards to two types of games: a synoptic board game, Strategious© which has been created independently by the author and a diagnosis card game which the author adapted for one of the modules he is teaching at the Swiss Hotel Management School of Leysin, Switzerland.

Following a deductive approach within a pragmatic ontology, this is a case study of the Swiss Hotel Management School of Leysin.

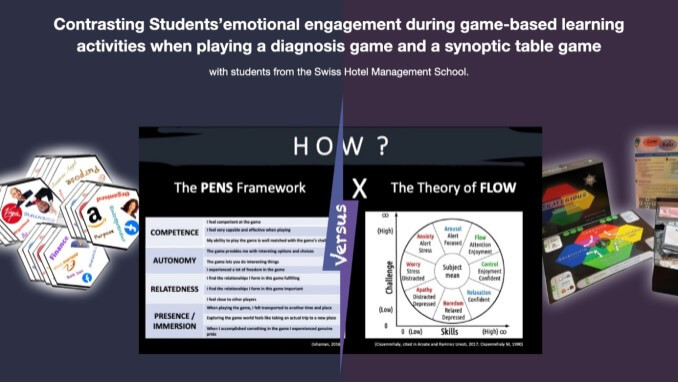

Participants filled a questionnaire adapted from the Flow model (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) and the PENS framework (Ichaman, 2016), and cross findings were put in relation with Toda’s gamification taxonomy, published in 2019.

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience is available on Amazon

The quantitative data collected by closed questions on a 1 to 5 Likert scale was analyzed using general proportions and cross-tabulations. The results showed players felt positive emotions as well as negative emotions with a board game. This was also confirmed by the PENS framework showing a better experience with the board game. Therefore, for game-based learning activities, serious board games can be qualified as emotional rollercoasters, whereas diagnosis card games can be qualified as emotional ice-breakers.

It was discovered that there were both generational and geographical variations in the emotional responses to the two games.

Context

This research assessed how participants perceived their emotional engagement during game-based learning activities, focusing on 2 game types. One game was a one-hour board game based on talent management, negotiation and strategic thinking. The second game was a 10-minute diagnosis card game on entrepreneurship, with famous entrepreneurs, their companies, and keywords from the module.

These games have been selected for this research because the author had already included them in one of his modules, called “Entrepreneurship in Events” in the final of the Bachelor of Arts in Hospitality and Events at the Swiss Hotel Management School, and he always wanted to know which type of game students preferred. The research was approved by the DEAN of the Swiss Hotel Management School.

Targeted issue

This research fits within a theoretical framework made from the model of Flow developed by Csikszentmihalyi (1990), which is defining eight emotions people feel when confronted by a task. The optimal emotional state has then been defined as the state of Flow. Jesse Schell (2015) further developed this theory by applying it to game design, saying that in order to keep a player engaged, a good game should constantly adapt the difficulty of the task to the evolving player’s skills. These two authors made a great contribution to the theoretical framework of serious games, but Melker (2015) suggested that more specific comparative researches were still needed to precisely differentiate between types of games. However, even if the theory of Flow developed by Csikszentmihalyi (1990) was thoroughly applied to game design by Schell (2015), it has still never been used to measure players’ emotional engagement when playing a game. Therefore, in the search of an effective measurement, the author decided to associate the theory of Flow with the recognized measurement, called the “PENS framework”, as the “Player Experience Need Satisfaction” applied by Ichaman (2016) and presented here below in figure 1.

Findings and Proposed solution

There is indeed a clear preference for synoptic board games but these findings also confirmed the importance of having a clear purpose and aim to support the integration of such game-based learning activities and diminish the students’ anxiety, relying more specifically on Mitgutsch and Alvaro’s Game System (2012). Moreover, the warning given by Toda et al., (2019) about the need of defining a clear purpose to game-based learning applies more specifically to generation Z students if it concerns a synoptic board game, and more specifically to generation X students if it concerns a diagnosis card game.

In regard to students’ culture, a greater care and purpose is needed for Americans students in case of synoptic board games, and for Middle East students in case of diagnosis card games which can be used as ice-breakers. Finally, such game-based leaning activities have revealed to be more effective with European students, in driving their perception to their emotional engagement.

Relevant innovation

Concerning the tool used to collect relevant data, in the search of an effective measurement, the author decided to associate it with a recognised measurement in the name of the PENS framework, as the “Player Experience Need Satisfaction” applied by Ichaman (2016) and presented below in figure 2.

Concerning the results of this research, the students showed a general preference for synoptic board games such as Strategious© which was included in this research. Board games produce a greater play experience in game-based learning activities (Hardin et al, 2019; Huang et al., 2019; Nakao, 2019; Sousa 2020). Going deeper, the author found that Autonomy and Relatedness were indeed more important for students when perceiving their emotional engagement when playing the board game than the card game. However, the research also revealed that students in general perceived a greater negative emotional engagement with synoptic board games. Therefore, the researcher has qualified game-based learning with a synoptic board game as an emotional rollercoaster with important emotional consequences on both sides. Furthermore, the diagnosis card game is safer although it generates less important emotional reactions from students, so it can be a relevant and safe emotional icebreaker.

Project outcomes & results

Therefore, the researcher qualified game-based learning with a synoptic board game as an emotional rollercoaster with important emotional consequences on both sides. Furthermore, the diagnosis card game is safer although it generates less important emotional reactions from students, so it can be a relevant and safe emotional icebreaker.

The cross-analysis revealed that students from X and Y generations perceived greater positive emotions (Arousal, Flow, Control, Relaxation) than students from generation Z with the board game, who are genuinely accepting more easily this type of game-based learning. However, with a diagnosis card game, students from generation X were the ones perceiving less emotional engagement. The author then saw a confirmation of the idea that each generation has its own socio-psychological perception (Vlada, 2020).

American students were more critical towards the synoptic board game as the results showed 20% of higher negative emotions with this type of game-based learning activity. This contradicts the report of Metaari (2020) which shows that the American continent is the first customer of serious games in the world and suggests that Americans would be more used to such activities, also supported by Ferreira et al. (2016).

Conclusion

The researcher has qualified game-based learning with a synoptic board game as an emotional rollercoaster with important emotional consequences on both sides.

The diagnosis card game is safer although it generates less important emotional reactions from students, so it can be a relevant and safe emotional ice-breaker.

With a diagnosis card game, students from generation X were the ones perceiving less emotional engagement whereas American students were more critical towards the synoptic board game.

The researcher suggests further researches to be conducted with different types of games and bigger samples to be able to create and share more exhaustive guidelines on how to integrate all types of games efficiently in learning.

References and further reading:

Burgun K. (2012) Game Design Theory: A New Philosophy for Understanding Games, CRC Press.

Chen Si et al. (2020) Games Literacy for Teacher Education: Towards the Implementation of Game-based Learning, Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 23(2), pp. 77–92. Available at [https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN= edsjsr.26921135& site=eds-live] Last accessed on August 1st 2021.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990) Flow, the psychology of optimal experience, Haper Perennial.

Gee J.P. (2005) Why video games are good for your soul : Pleasure and Learning, Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd.

Ijaz, K. et al. (2020) Player Experience of Needs Satisfaction (PENS) in an Immersive Virtual Reality Exercise Platform Describes Motivation and Enjoyment, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(13), pp. 1195–1204.

Liu, C., (2017). A model for exploring players flow experience in online games. Information Technology & People, 30(1), pp.139-162.

Rigby S., Richard R. (2007) The player experience of need satisfaction, an applied model for understanding key components of the player experience, Immersyve.

- Card Games or Board Games? - 24th October 2022

Be the first to comment