I was 12 when I first read about the lost city of Atlantis. The possibility of a whole continent, a whole civilization swallowed by the mighty ocean blew my mind and made me research for hours extensively using my 56 kb dial-up internet trying to find a satisfying answer.

But, that only lasted for a couple of weeks till I got exposed to Celtic mythology, then Greek mythology popped after, leading me to Nordic mythology after and the list just goes on with my never-ending fascination for myths & fantasia.

Fantasy are basically stories that predominantly depend on “what couldn’t be”, plus a dash or more of a strangeness element. They are stories that show grand measures of possibilities and extensive lengths a mere human can expand towards.

Yet, isn’t that the nature of all stories?

Quoting Janet Litherland,

“Stories have power. They delight, enchant, touch, teach, recall, inspire, motivate, challenge. They help us understand. They imprint a picture on our minds. Want to make a point or raise an issue? Tell a story”

Throughout my journey with game-based learning for the past 7 years now, I have always been selfishly satisfying my love for fantasia & myth in every game narrative created, because who really wouldn’t want to experience a story with unpredictable possibilities and journeys that can travel far off any of your usual mainstream borders. Stories can transform any traditional learning setting into unique experiences that intrigue learners to delve further, explore & learn.

According to David Perkins (a professor of Teaching & Learning at Harvard Graduate school of Education) for a learning experience to be effective & objective, we should apply some points within it:

- Learners must be deeply engaged with the subject matter

- Learners must undertake intellectual challenges

- Learners should have a room to take learning risks

- Learners must face a margin of failure

- Learners must have the ability to fail & bounce back

- Learners’ sense of curiosity must be increased

Stories already provide and fuel all the above points when weaved righteously within an educational game’s rich tapestry. Stories are sequences of connected events. Games can tell stories but also stories can be created through players’ interactions with games. Stories are can be told in a plethora of ways. They can be linear, nonlinear, or spatial; they can have a diversity of themes, tone, and objectives.

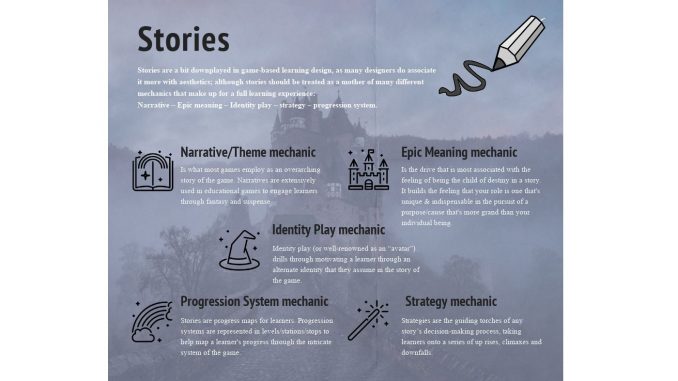

Nevertheless, Stories are a bit downplayed in game-based learning design, as many designers do associate it more with aesthetics; although stories should be treated as a mother of many different mechanics that make up for a full learning experience:

Narrative – Epic meaning – Identity play – strategy – progression system.

Narrative/Theme:

Is what most games employ as an overarching story of the game. Narratives are extensively used in educational games to engage learners through fantasy and suspense. A narrative can also be built on the principle of progressive disclosure. Rather than try to present a learner with a complex problem, narratives can be used to guide learners through a learning process and gradually let them encounter increased complexity.

Epic Meaning/Calling:

Is the drive that is most associated with the feeling of being the child of destiny in a story. It builds the feeling that your role is one that’s unique & indispensable in the pursuit of a purpose or cause that’s more grand than your individual being, such as saving humanity from an asteroid, or perhaps discovering the long lost art of alchemy. Meaning in the context of a game, can be tackled by giving purpose to the learning being attained; something that, when used, makes for a better sense of one’s imprint – even though it can be completely devoid of materialistic, or extrinsic rewards.

Identity Play:

On the other hand, Identity play (or well-renowned as an “avatar”) drills through motivating a learner through an alternate identity that they assume in the story of the game, which has multitudinous benefits that extend from evoking safety by buffer, and by shielding against personal loss, all the way to letting learners customize their own avatars creating a more immersive experience and a higher score on the ownership measuring stick.

An assumed identity can reach an enormous level of intricacy and complexity because a player’s avatar can assume the damage for them, shielding them away, and reminding them that it is not them being hurt in times of loss.

Strategy:

What is a story without strategy to it? Strategies are the guiding torches of any story’s decision-making process taking learners onto a series of up rises, climaxes and downfalls. Strategies make learners think about what they are doing, why they are doing it and how it might affect the outcomes of the game eventually.

Progression system:

Stories are progress maps for learners. Progression systems are represented in levels/stations/stops to help map a learner’s progress through the intricate system of the game. It is as crucial for learners to see where they can potentially go in the system as to see where they came from. This mechanic can utilize other mechanics such as PBLs (points, badges & leaderboard) as a representation of progress or a qualifier to a new level.

A story is a motherlode of mechanics that are all inter-related. There is no single mechanic that is developed separately from another in a story (if built righteously), since they are all interconnected and any change in one will have an impact on all others.

If, for example, the strategy mechanic was to change in order to offer a complex situation, that would possibly have an impact on the narrative mechanic, as the narrative would change to support the new strategy direction, while game progression system and identity play would also be impacted in order to integrate and highlight the change of narrative/ theme in the game.

In conclusion, games sure do encourage creative behavior and divergent thinking, (Fuszard, 2001) acting as learning triggers allowing learners to immediately take action, make meaningful decisions and volunteer to invest more and more time in the learning process, but all that wouldn’t happen profoundly without one epically engulfing story intriguing them one step at a time.

- A Quintessential Scheme for Engagement - 16th November 2021

- The Treasure of Atlantis – Story as Game Mechanic - 16th July 2020

Really i enjoyed, it’s a very good article.

Thanks for the article, Mohamed; I enjoyed it. The five categories are sueful for thinking about stories in different senses as the relate to games. I particularly like the point about identity, and the avatar acting as a kind of shield.

Stories as ways of making sense of the world seem particularly relevant to learning and learning games, because if we extend that that idea far enough (and I think we can), we reach the idea that almost no learning can happen without a story of some kind. Even Einstein balked when faced with a set of data (about quantum behaviours) that he could not make a narrative out of.

It’s interesting what you say about stories being downplayed as aesthetics; I think that’s often true. I agree it can be wrong-headed, as learners will often make a narrative as a way to try to make sense of things if you don’t, so you lose the chance to influence that narrative if you leave it entirely to them.

I find it interesting to think about abstract games such as chess or go in this context. They can be much fun to play and do teach us some things like strategy, use of space, but (a) they don’t perhaps teach us as much real-world transferable stuff as some less abstract games where we remember the narrative, and (b) when they do teach us, it’s often because we did put a narrative on things (about the ebb and flow of the game for instance, and its strategy).

Really interesting approach: Story as a mechanic. Many game designers argue how to start the game design process. What should be the leading attribute of the game: mechanic, theme, graphics, story, etc?

In reality I believe we all mix these attributes until we break some and end up with some that work. Then start again 🙂

Thanks for the article.

Very insightful article tackling many issues in learning and development. I am looking forward to more articles . Well done .