This article was originally published on the Octalysis Group website in March, 2019. The original article can be accessed at the Octalysis Group’s website . Chris hopes to follow up soon with analysis of the new Kimmy Schmidt interactive special.

Netflix has always employed elements in their design that can be found in games that help make users glued to their screens. Now they are taking Gamification to the next level with interactive storytelling. But does the new approach get users hooked? Let’s check the results!

First let’s talk about the Game techniques Netflix has already implemented well and that are key to the addictive nature of this platform.

The Alfred effect (Game technique #83)

This is, “When users feel that a product or service is so personalized to their own needs that they cannot imagine using another service.” Netflix gathers data on what you watch, how long you watch it, and what other people who watch what you watch, watch. It aggregates and parses through all this data to create personalized recommendations of categories and films you might want to watch. Want to feel just how powerful this technique is? Just boot up your friend’s (or a stranger’s) Netflix and you’ll feel a discordant alternate-universe version of a Netflix recommendation engine.

Cliffhangers

Netflix encourages users to binge their content by structuring the content so as to leave the unanswered question of “What will happen next?” in the users’ mind at the end of every episode. This activates Core Drive 7: Unpredictability and Curiosity and causes users to want to watch the next episode, “Just to find out.”

Netflix isn’t the only one who does this of course. Many forms of media utilize cliffhangers. But, Netflix is so good at this and so known for it, they’ve become synonymous with user’s binge-watching whole seasons of shows they release.

Autoplay

At the end of a piece of content, Netflix defaults to automatically playing the next piece unless the user opts out. This means the user has to overcome both inertia (Core Drive 8: Loss and Avoidance) and their innate motivation to be curious (Core Drive 7: Unpredictability and Curiosity) to stop the experience.

Netflix gets interactive

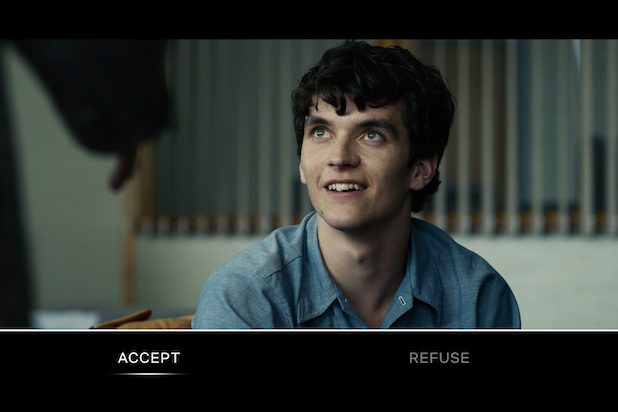

Over the holiday season, Netflix released Bandersnatch, which is a choose-your-own-adventure (hereafter known as CYA) experience adapted to its platform. While CYAs are not new, this is the newest expression of them using up to date technology. In pre-internet days, CYAs were contained in books. Now they are common in games such as TellTale’s The Walking Dead or Detroit, Become Human.

Bandersnatch is an “episode” in the series Black Mirror, which is like the Twilight Zone for the smartphone generation. The word “episode” is in quotes because it’s like an interactive netflix hybrid of show and game.

This experience uses two major game techniques here that other content on their platform (or any streaming platform) haven’t used:

Choice-based narrative

Every 5 minutes or so, the user is presented with a choice. There is a default choice, so it’s possible for them to simply watch the story as a movie. But, they are triggered through the onscreen UI (two choices presented with one highlighted by default) and via the narrative itself. A character says, (paraphrased) “So what’s it going to be? Frosted flakes or Sugar puffs?” as one of the first choices.

Countdown timer

The feedback mechanic is a slowly decreasing line at the bottom of the screen. This is a common Black Hat technique that creates a feeling of urgency in the user, which makes them want to act fast. These two techniques have been used to great effect in dialogue-driven video games in recent years.

Why now?

Introducing this “new” form of storytelling and engagement is a shrewd move by Netflix. Netflix faces fierce competition from both other streaming platforms, as well as users moving to more interactive types of online content.

As Netflix’ licensed streaming content continues to get prohibitively expensive, they continue to invest more in data-driven original niche content to keep their subscribers happy.

But other streaming platforms, such as Amazon Prime, Hulu, and Youtube can do this too. And soon Apple and Disney will join the fray. This has created an arms race of content creation, or what we consumers call, “Peak TV” The problem is that there is a hard cap on the amount of content consumers can consume, so at a certain point, increased content stops becoming a market differentiator.

And games are dominating more and more of users’ attention. A recent earning statement (Via Forbes) from Netflix claimed, “We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO.”

So Netflix is right to start adding interactive elements to their narrative. Now they all need to think different to stay ahead of the curve.

The challenge of gamifying narrative content

There has been userbase backlash. Many users see this type of storytelling as just a gimmick and that having choices reduces the meaning in the narrative. We know that to effectively motivate users through Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity and Feedback, choices need to have influence on how the story unfolds and show the immediate effects of strategic decisions. In other words, choices need to be meaningful.

But Netflix’s business model may likely run counter to creating narrative content with true meaningful choice.

CYAs are fundamentally more expensive to produce. In a modern CYA book such as Romeo or Juliet, there can be 800 endings. But, in Bandersnatch there are just 8. And even so, the script for Bandersnatch was 170 pages long, which roughly equates to 170 minutes of content that needs to be created. A normal episode of Black Mirror runs about 60 pages.

Because users can take multiple paths through the content, each user may only experience half or less of the content that is produced. More branching paths to the story means more potentially unseen content. Unless of course, choices don’t matter…

What if the choices aren’t meaningful?

Leaving out procedurally-generated storytelling (such as the Nemesis system in Shadow of Mordor/War games), the content business doesn’t scale unless users are offered only the illusion of choice. Instead of a truly branching narrative, with endless possibilities, the choices must lead back to the same set of outcomes.

Bandersnatch, to its credit, tries to deal with this problem in the narrative itself. The story centers on a character who is trying to create a CYA game of his own and is dealing with all the same problems (in a meta way) of Netflix. By lampshading the limitations of this form, the content creators hope to make the lack of meaningful choice more thematically connected. It makes it feel like less of a cheat, because the user understands why their choice is less meaningful.

But, this creates a bigger problem. Bandersnatch might be a test-run to see if these an interactive Netflix niche can become part of their unique offering in the market. But, most shows that they offer are not thematically linked to this content form. So, while it might work in this case, what happens if they try to apply this to romantic comedy? A documentary? A biopic?

Netflix is already trying again, this time in the survival genre with You vs Wild. Will this be another flash in the pan gimmick or will it be the beginning of new popular trend in Netflix’s arsenal?

Suggestions for Netflix

Here are some things that Netflix could do that would make this interactive content more effective.

Implement more explicit gamification

In part of Bandersnatch, users attempt to open a safe that has a password. They can only learn the password through watching certain parts of the branching narrative and they can learn of more passwords by watching more of the story. They could lean on this even more by hiding codes inside the storytelling itself.

This means that users who want to see all the content have to re-watch the story like a puzzle. Instead of offering branching narrative as the main source of engagement, easter eggs and secrets like this could extend the shelf life of a product. Bandersnatch was already seen as a puzzle by an army of redditors, who mapped the entire flow chart of the story within days of Netflix releasing it. Creating mysteries like this must take the collective intelligence of internet detectives into the mix and scale the problem accordingly unless they want their hard-earned puzzle to be figured out within hours of their content being released.

Crowd voting

Instead of creating lots of different branching narratives, Netflix could release content in discrete episodes. Where the story goes next could be voted on and users could see how others voted. This is essentially taking the mechanics of American idol-style shows and applying them to narrative on a streaming platform. This would work better in a show with a short production time or a show that was cheap to produce, such as a mockumentary.

Shift the framing

Tell the user up front that their choices will be recorded and given to them later. This means that their choices are empowering because they tell themselves something about the user, not that they actually impact the story. This is using the same underlying motivation used in quizzes like “What Game of Thrones character are you?” These choices could then be shared with other users or pushed to social media to generate buzz.

Use Moats (Game technique #67)

Moats are skill-based pass/fail states. Think of a boss battle in a game. The goal is to test the user’s knowledge of the game mechanics. If the user fails, they have to play the level again. In an interactive Netflix example, users could be asked questions that depend on things they’ve seen before. If the user fails, it causes them to pay more attention next time, which means the content must be rewatched.

Of course, these ideas would have to be properly designed with motivation in mind. Netflix, if they are smart, are just getting started in incorporating gamification in their offerings in order to stay ahead of the curve.

References and further reading:

The Alfred effect (Game technique #83) – a game techniques which makes users feel that a product or service is personalized to their own needs.

Check out this great video on designing crossword puzzles to see how to effectively hide codes in the storytelling itself.

Check out this video on procedurally-generated storytelling

Great analysis. I had been thinking some of those things about Bandersnatch. In many ways it was the ideal test run. But I fear that long-term, Netflix will go with the less-meaningful choices option.

Another way this could work quite nicely could be to shift the frame from ‘you follow a character and your choices are their actions’ to something more like, say, a choice-based version of Pulp Fiction, with overlapping narratives. So the choices would be more like who to follow, rather than changing the story. This would lead to less of the feeling of repetition I got when re-watching loops of Bandersnatch, and maybe more completism from people who need to find out what happened to each of the characters. If this was plotted really well, all of the characters stories, majjor or minor, could be really compelling — like for instance when Rosencrantz & Guildenstern are dead takes two minor Shakespeare characters and makes then interesting, and then even when what you watch in the play is just part of Hamlet (which you’ve seen before), it’s imbued with new life because you’re seeing it as part of *their* story, rather than part of Hamlet’s.

Thanks for the tip on Romeo and/or Juliet; for some reason I had missed this (which is poor for somebody who had the first 20 Steve Jackson & Ian Livingstone books) and it looks great — I just ordered it.

Talking of Steve Jackson, Terry. Have you seen Inkle’s ‘Sorcery!’ games? https://www.inklestudios.com/sorcery/

That has been on my radar for awhile; I did the first two in book form so it’s due a finish; thanks for reminding me.