Playing video games solo is often the default mode. I can’t count the times I’ve picked up a console game from my playing past, and then been disappointed to remember that playing ‘together’ means watching while others play.

Tabletop games on the other hand, are, or have been, generally social affairs. There are games that are specifically meant for solo play, Patience card games, for example, but finding a one-player game in your local games store requires a little more searching than finding a party game, or a 2-4 player game.

But we can’t always find others to play with, and the pandemic has made that problem more prevalent. This has led to the recent rise in ‘Automa’, both ‘official’ – included with commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) games when they are published, and ‘unofficial’ fan-built solo play systems.

What is an Automa?

An automa simulates an opponent in a game. You may sometimes hear it referred to AI, but in reality, the ways that different automa work differ a lot. Some may make use of the game’s resources and mechanics (a more AI-ish characteristic), while others simply allocate actions to the ‘opponent’ at a similar rate to which a real opponent would play – less ‘intelligent’.

The term was coined by the man who is arguably the most famous automa designer, Morten Monrad Pedersen, while he was creating a solo game version for Viticulture, Stonemaier Games’ wine-making game. Following that he founded The Automa Factory, which works with other games design companies to create solo game versions of their games.

Viticulture is available on Amazon

The Automa Factory work extensively with Stonemaier Games, and many of the games listed below come from their stable. Their automa are simple to use, and are based on a small deck of cards. In Wingspan, for example, a card is turned over from the deck each time it is the automa’s turn and the action listed on the card (from one of four sections, depending on which round of the game is current), are carried out. End of round scoring is implemented through a ‘base value’ of a resource printed on the automa card, added to the number of action cubes on the current round’s goal tile – removing these cubes may be one of the automa actions that is taken in a round.

There is even a really simple mechanism for varying the Automa’s competiveness, by changing the number of points it is awarded at the end of the game for each face down bird card – and by including the ‘expert’ level automa card ‘Automubon Society’.

Wingspan is available on Amazon

The automa in Wingspan has much reduced capacity for action compared to a real player; does not have a player mat, does not collect food tokens, does not pay for anything, does not benefit from bird powers and collects birds and eggs only for the purposes of game end scoring- a charactieristic known as ‘streamlining’. Nevertheless, given that the winning condition in Wingspan is a final score, it can still win.

Automa as AI and other methods

But the Automa Factory cards is not the only approach to creating automa. If you take Board Game Geek’s geeklist definition of an automa (and why not), it A) stops short of being a full AI simulation, and streamlines out much of the complexity of those, B) should be able to win or lose in much the same way as its human opponent, and C) does not require decision making or intervention on the part of the human player for it to work.

Several games that were submitted to the automa geeklist have been removed by the list owner for failing to meet these criteria. For example, Power Grid: The Robots, lost its place for including a full simulation rather than a streamlined experience of playing an opponent. Imperial Settlers lost out because it changed the experience of ‘losing’, so that it was not the same as losing to a human opponent, and Churchill was excluded because it was not sufficiently automated, and required players to come up with ideas of how to play the opponent.

Perusing the list of games which remain reveal a wealth of different ideas for implementing solo play, and for the sake of completeness I also include some games which might have been excluded, purely because the mechanisms used might be interesting and useful to readers of this article.

Just play – Some games, most likely cooperative games, have no opponent as such, so solo play is simply a case of playing on your own. Terraforming Mars is a good example of this. In the official, included, solo version, it says that you have a ‘neutral opponent’ from whom you can steal resources and so on, but as they do not ‘play’ this is simply a case of taking those resource from the stockpile. In reality, you just play alone, and your only opponent is time – you are limited to 14 generations in which to achieve the triple goal of terraforming. This of course, does not really qualify as an Automa. It is certainly ‘streamlined’ (in that it reduces the need for actually carrying out the game actions), but is in fact so streamlined that is effectively the same as having no opponent at all.

Terraforming Mars is available on Amazon

However, there are some inventive fans of Terraforming who have stepped in to remedy that shortfall.

The cards for a fan-developed ‘AI’ type automa for Terraforming Mars along with the English version of the rules, and the French version too.

Ark Nova – arguably the stand out game of 2021-22 also comes with a built in solo mode, but it attracted a fair bit of criticism from players for being overly rigid, and therefore not replicating the experience of playing against a real opponent. The Geeklist features a couple of fan-built automa including ARNO – which must be one of the most compact automa around at only 5 cards. It uses a simple selection of decisions using dice. Several ARNO bots can be used in a game – to add a 3rd or 4th player in a two player game, and they can be played at differing difficulty levels. Unlike many automa, there is quite a high degree of interaction between players and automa, as ARNO can move cards in the display for example.

However, the prize for the most compact automa I have played must go to the fan-built solo play version for Snowdonia, which uses only the materials which come in the box and a six-sided die. This is an example of the randomiser style of automa, and places game resources according to the die roll and the availability of spaces on the board.

Snowdonia is available on Amazon

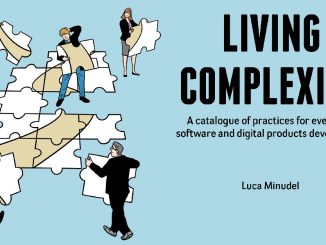

Designing Automa as a learning practice

The most obvious reason for creating automa would be to be able to play a well-loved game even when there is no opponent(s) available, but the process of creating an automa has value within itself.

The process requires that the automa designer studies, and really deeply, understands the mechanics of the game they are trying to ‘automate’. While the resulting materials which actually implement the automa may appear simple, the work behind them is not. Ironically, the more compact the output, the more hours of work have probably gone into the processes of:

- Streamlining the actions of the ‘opponent’ so that players do not have to ‘play the part’ of the automa

- Ensuring that the use of an automa does not overly restrict or change the experience for the player

- Thorough playtesting to make sure that the behaviour of the automa remains congruent in all likely game situations

- Ensuring that a win state can be reached despite the streamlining

- Ensuring balance in play that replicates the play of human opponents (that it is neither too hard or too easy to beat the AI)

In recent years, games-based learning has moved beyond creating games for learners to play, to offering the experience of games design itself as a valuable learning opportunity. The design of an automa for a particular game is a decidedly non-trivial task, which could provide learning in design thinking, systems thinking and mathematical modelling – as well as any learning related to thematic aspects of the game.

The benefit doesn’t only extend to learners. As a practice for games-based learning practitioners themselves, automa design can be a way to really grok how a game works, maybe with a view to modding for a particular learning outcome, or to explore how to design your own game using similar mechanics.

Games-based Learning and Automa

In practice however, many GBL practitioners do not have the time, to play with creating automa without a specific (commercial) goal in mind, so why might you want to think about creating solo play versions of your existing (learning) games, or indeed, commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) games that you use in your learning practice.

The pandemic meant that many of us who used tabletop games in face-to-face settings, had to adapt those experiences to online environments. In many cases, and to many people’s surprise, this worked remarkably well. However, in other situations, there was a definite feeling of having ‘lost’ something. In those cases, it might well be better to offer learners the opportunity for a solo (physical) learning game experience, rather than a ‘less good’ online shared experience. Any non-game aspects of the learning (e.g. debriefs, planning and so on), that require people to actually get together, could still be implemented through online meeting rooms etc. It gives the GBL practitioner another option to offer the play, other than simply ‘f2f together’ and ‘online together’.

Asynchronous learning has often been carried out in online settings too. Where games-based learning has been used asynchronously, tabletop gaming has never really been considered. Well-designed automa would open up the market for physical games in asynchronous learning settings, and would also give distance learners the opportunity for learning through interaction with “others”.

- James Bore – The Ransomeware Game - 13th February 2024

- Ipsodeckso – Risky Business - 23rd January 2024

- Review – Luma World Games - 15th December 2023

Be the first to comment