– the case for alternate reality games and narrative-making play

Most games don’t pretend to be real. As a player you sit around a table holding cards or moving pieces, or stare at a screen mashing buttons on an oddly shaped controller – actions that are different from what’s going on in the game narrative. If the game represents reality at all, it’s some remarkably small subset of reality, and there are layers of abstraction between you and that sliver of a world. Playing Settlers of Catan could never be confused with the actual experience of colonizing an island.

And yet: many games do carry a layer of verisimilitude. Even chess, a game in which the abstraction layers are about half a mile thick, can echo the emotional struggles of waging war. A person playing (losing) at chess can still feel emotions about it (crushing pain) half a century later – a ludic echo of PTSD? (Don’t ask me how I know this.)

So a game about X is barely like the real X, nevertheless it can still be evocative of the experience of real X in meaningful ways. That’s the allure of serious games. But what if playing a game about X was actually a lot like living the real X? And still be a game, not a simulation? Come closer, children, and let me tell you a story or two…

Unavatared play and liminal identities

Most games feature avatars – the representation of the player in the world of the game. You are a meeple on a gameboard or a sprite on a screen. As game abstractions go, this avatar is probably the most profound one, because it’s messing with your identity. You might be the most fiscally responsible person in the world, but in Monopoly, if your token lands on my hotel on Park Place, you will bankrupt yourself. A game avatar inevitably signifies that some aspects of your personal identity are not relevant; this is problematic.

Many games use this identity shift as a feature. You are not a robber baroness or a fey elf, but you get to play one in Catan or Dungeons & Dragons. This is role-playing in games. Note that role-playing doesn’t eliminate problematic aspects of avatared play, it just normalizes them.

To me, role-playing gets interesting as it gets less avatared – when it encourages you the player to inhabit not a foreign identity but a liminal one, one that maps to your actual self. So, for example, you play a character that’s a lot like you except less afraid to take chances. Or you take on the worldview and goals of a real-life opponent of yours, to walk an uneasy mile in their moccasins.

But, you say. It says “alternate reality games” in the title of this article and we’re half a dozen paragraphs in and you haven’t got to even mentioning them yet? Ah, good point. I did promise you a story or two. Here we go:

Collaboratively creating the Global Oil Crisis of 2007

Once upon a time, in early 2007, a motley group of U.S. citizens had an inkling that a global oil crisis was looming. As you do. There was no Facebook/Twitter/Insta back then, so to prepare for the crisis they set up their own citizen nerve center at worldwithoutoil.org and spread word about it “just in case.” So, when the crisis did begin on 30 April that year, they were ready to receive the citizen reports about the crisis that began to flood in from across the U.S. and around the globe. As hundreds then thousands then tens of thousands of people began to interact with the site, a unique massively multithreaded narrative of the crisis began to emerge. Reviewer Nina K. Simon described it:

“It is a far cry from the “calculate your carbon footprint” or other casual games about resource usage. It required much higher engagement than reading news articles on the topic; [World Without Oil] was a huge growing, twisting network of news, strategy, activism, and personal expression.”

World Without Oil was an alternate reality game, or ARG. The motley group of citizens were characters played online by gamerunners, and worldwithoutoil.org was the portal to the alternate reality of the (entirely fictional) oil crisis. The people engaging in the game played along with the fiction, telling how the crisis would be affecting them as though it were really happening. And, you’ll notice, it was unavatared play. The game didn’t ask you the player to change; it changes your world instead. Whatever defines you – your wit, your art, your feels, your imagination – you could bring to the game. And this openness enriched the game’s massively multithreaded narrative. The players’ collective story arc, which initially was full of individual stories of disruption and chaos, pivoted to shared practical ideas for adaptation and resilience.

World Without Oil showed that an alternate reality-style game about X can be very much like the real X, and thus more verisimilitudinous and meaningful to its players. An authentic fiction, if you will. Player OrganizedChaos explained the game experience succinctly:

“It was real to me.”

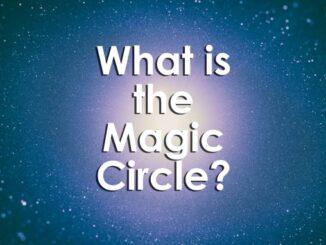

Games reaching out into your life

Every game has a “platform” – the magic circle in which it appears. Football has the football field, chess has its board, and so on. In storytelling games the physical platform can disappear entirely: the game is taking place entirely in the shared imaginations of the storytellers. In alternate reality games such as World Without Oil, the entire world is the platform. Thanks to the Internet, anything can be in the magic circle: players transport the fictional oil crisis to their back-yard garden in Toronto, gas station in Atlanta, residential street in Marseilles, and so on.

World Without Oil, then, had “pull” immersion – once the game idea was in your head, you the player could freely pull signals of the game story from the real world around you. Alternate reality games rise to next-level immersion if the gamerunners can add “push immersion” – if they can arrange for the game fiction to manifest itself in the real world. A classic example: the calls to phone booths in the I Love Bees ARG (2004). In the fiction of that game, a damaged Artificial Intelligence from the future had crash-landed to Earth and, in trying to figure out what had happened to it, was ringing public pay phones (a few still existed then). So that game, which could otherwise seem esoteric and virtual, elegantly pushed itself into the real world to make the experience more immersive for its players.

FutureCoast (2014), an alternate reality game about climate-changed futures, also featured pull immersion. In the fiction of that game, the Internet of the future had developed a file leak. The gamerunners created physical representations of these bits of leaked data – crystalline artifacts – and cached them in public spaces for players to find. When a player successfully recovered a “chronofact,” they (and everyone) were rewarded by a new glimpse of the future… a chunk of leaked data…

…which, as it turns out, was a voicemail. The leak was in the voicemail system of the future. Which may seem, um, underwhelming? Maybe. But here’s the transcript of one:

“Hi, honey. It’s Mom, I was just thinking about your visit and about when we talked about how hard your pregnancy is, and how you’re scared of bringing a new person into this world when everything feels so uncertain. Yeah I told you when we talked I felt exactly like you when I was pregnant with you, so, I’m pretty sure every mom felt that way and you’re definitely not alone. -But honey I think that you might wanna move somewhere with a better water supply and farmable land nearby. You know we definitely got it up here and I would love to help you take care of that baby. So, you know, why don’t you guys talk about it. I know that you guys have your jobs and your friends and everything in Southern California but it might be time to think about moving somewhere that’s gonna be a little safer and easier while you’re bringing up that baby. Ok sweetie I love you thanks for those pictures and call me after you’ve had your next check up. Bye-bye.”

The chronofacts were a “rabbit hole” that helped bring people to imagining, and ultimately creating, visions of possible futures. People would listen to one, then another, then another, of the messages that people will be leaving for each other in the years 2033, 2041, and so on. Ultimately the listeners discover that the voicemails they are hearing were created by people just like themselves. There was a 800 number to call, so they could contribute their own voicemail leaked from the future.

As did World Without Oil, the FutureCoast ARG seeded a fiction that was then grown into something big by its players. By the time the project ended, it had amassed over 500 voicemails, more than you could listen to in a day. Collectively the voicemails built up a guidebook to climate-changed futures that supplies all the texture and context that I find lacking in statistical projections. FutureCoast was an engagement engine for storytelling – a way to encourage people to think about the future and participate in its shaping.

That time you rage-quit high school

Earlier I said that ARGs don’t require you to change your identity (as role-playing games do), and that’s true. But at the same time, ARGs don’t require you to keep your identity. As a player, you can slide easily into a liminal identity (one adjacent to your current concept of self), and players often do.

In 2012 an ARG called Ed Zed Omega explored the values and shortcomings of American education, especially in high school. It did so by embodying a common liminal identity for American young people: the escapee. In Ed Zed Omega, in live events and on the internet, seven young actors played the version of themselves that actually did act on their dissatisfactions with school and walked out. In real life, when a young person leaves school, it happens quietly; in Ed Zed Omega, the students dropped out loud.

Once again we find an ARG that seeded a fiction that players grew into a unique narrative about U.S. education today. The provocative, transgressive characters created a space for voices not normally heard in debates about what we teach and how and why. The Zed Omegas encouraged unavatared play and, when they appeared live, were a landmark example of the power of push immersion in narrative-making play.

Authored and unauthored narratives

I don’t know why we enjoy authored narratives so much. Maybe because they’re characterized by the things – plot, arc, characters, an ending – that we don’t have in the stories we tell about our real lives. These days, when I sit down with a friend (on Zoom, alas) and we catch each other up on our lives, the stories often sound like just one damn thing after another.

When it comes to stories that help us make sense of our lives, I find that authored narratives fall short. The author is going to bend messy reality to advance the plot and pace the action and give us the sense of an ending, and that’s not what we need. We need to hear all those voices spinning out all those multiple threads of possibility, in huge growing twisting networks of news, strategy, activism, and personal expression.

I wish I could point you now to Thirteen Patient Zeros, an ARG in 2017 about a global pandemic. But to be clear, I can’t. We didn’t run one. We didn’t have thousands of people globally imagining what they would do if an infectious disease with asymptomatic transmission was starting to spread across the globe. I wish also I could point you to Whose Streets?, an ARG in 2019 about the rise of fascism and paramilitary threats to U.S. democracy. To be clear, I can’t do that either, because no one ran one. We didn’t play these things first, and now we must live them.

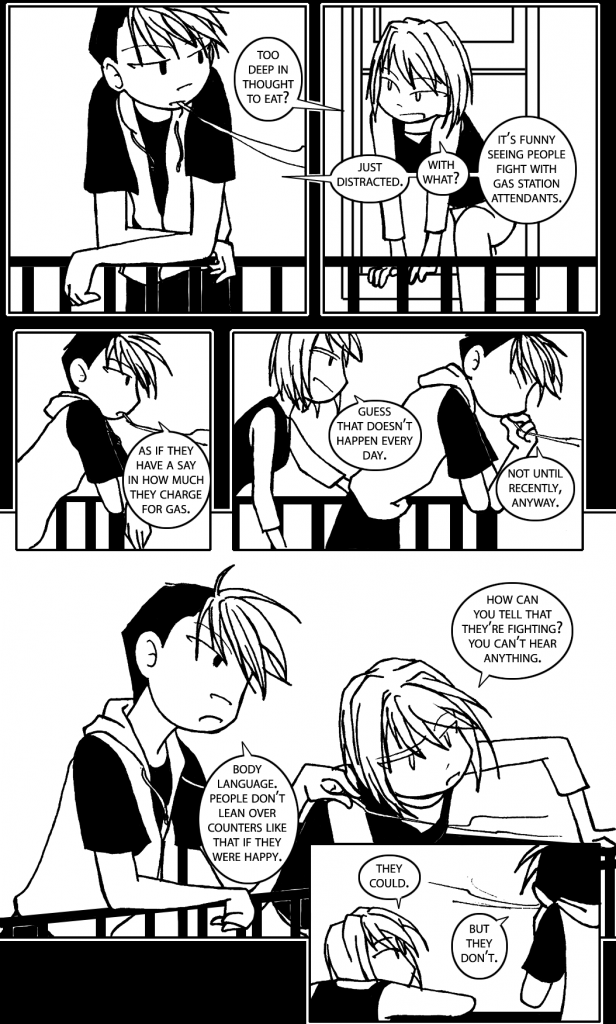

Page from the World Without Oil webcomic series by player Anda (Jennifer Delk). Courtesy of the artist

- ‘Play it before you live it’ - 20th July 2020

Hi Ken. As you know, I have been a long time admirer of what you achieved with World Without Oil. In fact, it continues to inform my learning design practicealmost daily. This article is great because it really adds to my understanding of the experience of both creating and playing such experiences. I especially like the idea of liminal identities – someone who is me but not quite me. This will be so useful in creating learning experiences around activism and behaviour change. One of the challenge for many learners in areas such as Climate Change, Systemic Racism etc. is that they feel powerless. I can see now that one of the key points of design here would be to allow the learners to inhabit personae which are them, but more empowered.