As long-time youth program developers, several years ago we became curious about game design, inspired in part by Doris Rusch’s work on deep games.[1] In Making Deep Games and her TEDx Talk[2], Rusch describes how she uses the game design process to more deeply understand lived experience, both her own experience and others’ experiences. Designing a game as a metaphor for rich and complex experiences—from depression to eating disorders to sexual abuse—creates a concrete opportunity for someone else to interact with that experience. The game serves as a pathway for understanding, an opening for connection. Games can be a powerful tool for facilitating empathy. What’s more, understanding one’s own lived experience through the process of designing a game to represent the systems harboring the rules and roles impacting that experience can be transformative, cultivating self-awareness and an understanding of how being embedded in a system influences one’s own thoughts and feelings.

Could the process of game design be used with teens to support meaningful and creative learning about the self and the world? And might this process activate teens’ natural creative energy and inclination toward exploration to identify ways to change the world for the better?

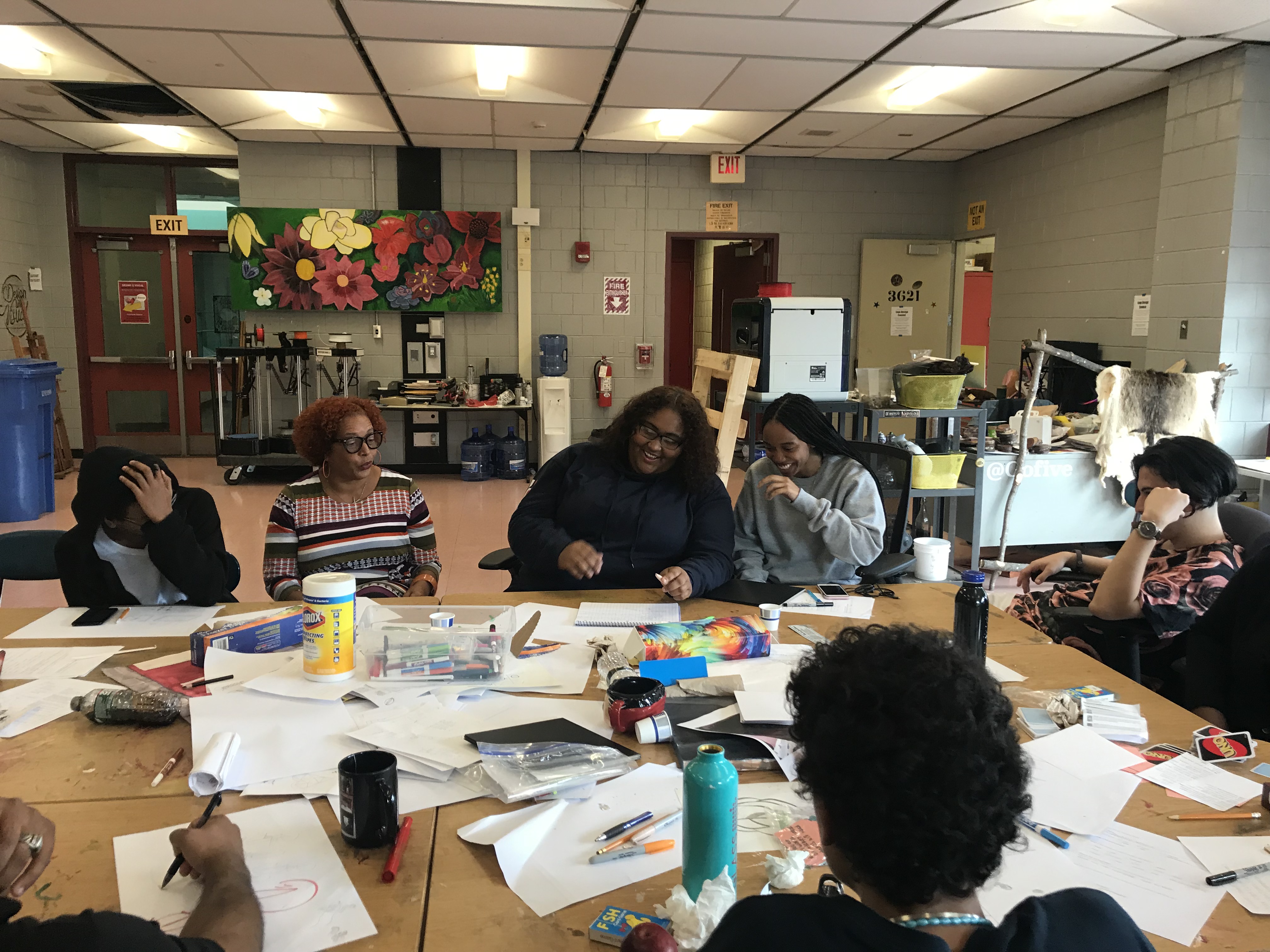

To find out, we created Game Design Studio, a co-design experience that uses game design to further teens as creators of knowledge, individuals who have a real ability to contribute to meaning-making and surfacing of solutions. Teens work in codesign on games that both represent their lived experiences in the world and worlds they imagine, worlds that are designed to better meet their needs and support their thriving. By creating games through this process, we believe, teens will help to shape in important ways how teachers, educators, parents, and policymakers view the potential and needs of teens. And in this way, teens are changemakers.

Empowering teens as changemakers means engaging youth and communities in drawing on the past and present to create new knowledge. This positions teens not merely as end-users or consumers of programs, but as creators both of knowledge and action steps to begin the work of building healthy, equitable, and sustainable communities.

Structure and Experience

Designing games—like making a painting, composing a song, or writing a poem—is an act of self-expression. Unique to game design is designing a system with rules, roles, ways of progressing, and win and loss states. We use game design as a way to engage youth in thinking about their lived experience, how they think about and understand the world, and what they might like to be different in their world and how they would go about making that change. Synthesizing their imagined change into a structured game that others can experience supports youth designers in thinking concretely about the specifics of the change.

Through various structured and open-ended activities, we explore questions such as: How do you feel in the current state (your lived experience) and how would you like to feel instead? What would need to change about the rules, roles, ways of progressing, and win and loss states in your own life to feel that way you want to feel, as opposed to the way you do feel?

Engaging Communities

Games create experiences to engage community in empathetic immersion. Youth game designers learn to balance player agency and uncontrollable constraints to shape the emotions of the player and help others tap into their experiences. At a recent Game Design Studio in Boston, teens shared their experiences with re-entry after contact with juvenile justice social service systems. They created a re-skinned version of Sorry called The Runaround, complete with parole violations, family setbacks, and missed fines. The Runaround is frustrating to play. As soon as you get some pieces out you find yourself sliding back to the start. Players feel the stress, sadness, and frustration teens feel trying to get home and stay home. Though the game rarely has a winner, players have a chance to talk about how the systems designed to serve youth can better meet their needs. Adults take the experience of playing The Runaround with them when they return to institutions and agencies positioned to make a difference in services to support teens.

We believe this game design studio process lays a foundation to support social change, and it includes guiding teens in critical reflection to build hope and self-efficacy related to the possibility of system change. Teens think about and explore through gameplay and game design techniques the design of systems that impact their lives, the interpersonal and sociopolitical processes that perpetuate those systems, and the leverage points that have the potential to change interactions and processes for the better. This serves to prime youth to see their potential as change agents in the communities to which they belong. It can also support their integration of individual-level and community-level empowerment by informing those in power about helpful actions they could take to improve interactions with and experiences for disenfranchised teens.

Game Design Studio creates important spaces for learning and growth, lessons that should be shared with the teens’ communities. The encounters end with game showcases, inviting adult stakeholders—administrators and teachers, social workers and principals—to play the games the teens have designed, and talk with teens about how to make the community one where teens have a seat at the table on issues that affect them.

Games designed by teens offer a doorway to what is like to be a teen today. Rusch[3] writes, “Games can communicate deep messages; they can make us think and feel deeply; and they can move us in a way no other medium can because games enable embodied experiences.” When we play a game, we interact with the game world, learning how the world works as we act upon it. When adult stakeholders play the games youth designers have created about their lived experiences, the adults experience how rules and roles are experienced by young people. By design, the play may evoke in adults feelings of unfairness, injustice, joy, inspiration, or frustration. Teens have a chance to learn from each other, exploring their peers’ prototypes and sharing feedback and learning with each other. Long after the Game Design Studio is over, teens and adults can continue to dialogue about the issues that matter to them, playing and working together to help teens thrive.

References and further reading:

[1] Rusch, D. C. (2017). Making deep games: Designing games with meaning and purpose. New York: CRC Press.

[2] Rusch, D. C. (2017, May 22). Why game designers make better lovers. TEDX Talk, DePaul University. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHrTbF9cKEc

[3] Rusch, D. C. (2017). Making deep games: Designing games with meaning and purpose (p. xx). New York: CRC Press.

- Imagining a Better World: Game Design with and for Teens - 17th April 2020

- Imagining a Better World: Game Design with and for Teens - 17th April 2020

Doris Rusch’s work is exceptionally insightful, especially in terms of teens:

“Games can communicate deep messages; they can make us think and feel deeply; and they can move us in a way no other medium can because games enable embodied experiences.”

Really appreciated the perspective presented by Dr. Susan Rivers and Susan Jane.

Rusch is always an excellent reference when you come across people who challenge the idea of using games for learning as ‘trivial’ or childish. I really enjoyed looking again at her TED talk when we received this article.