Artists are often described as people who “see differently”. What if that difference is not mystical, but methodological? What if the processes embedded in artistic practice — layering, reframing, composition, iteration, and the types of ‘seeing’ involved in observing subjects and making art, are forms of disciplined thinking that can be made visible and shared?

As part of developing a participatory art methodology, I am exploring whether specific artistic processes may strengthen particular thinking capabilities. The following small selection of proposed activities are hypotheses about the link between art seeing and making and cognitive modes and capabilities, containing working assumptions that will be tested through participatory research.

Emotional vs Structural Reading

An appreciation exercise. Participants first respond to prompts designed to elicit emotional reaction. What does this feel like? Where does your eye settle? What mood is present? They then shift to structural analysis: How is the composition constructed? Where are the weight, balance and directional forces? How is this work put together? What processes and techniques can you infer?

This dual reading is assumed to strengthen integrative thinking, the ability to hold emotional and analytical interpretations simultaneously. It may also support metacognition (awareness of how we form judgements) and cognitive flexibility, as participants consciously switch interpretive modes rather than collapsing one into the other.

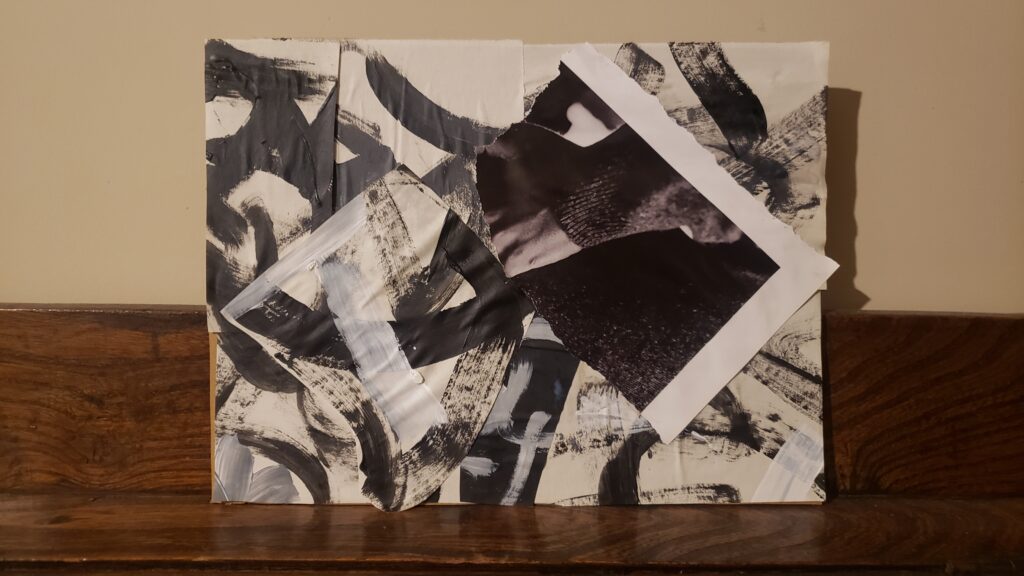

Iterative Collage for Composition and Value

Participants create rapid abstract collages focused on composition and tonal value. The pieces themselves have been made using a limited palette of black, white and greys and rapid mark-making. Pieces are rearranged, reduced and rebuilt across several iterations.

This process appears to model problem solving through visible trial and adjustment. It may also strengthen critical thinking (evaluating what works visually), reframing (restructuring rather than discarding), systems thinking (understanding relationships between parts), and prioritisation (deciding what to remove or emphasise). Because collage allows quick change, it encourages iterative evaluation and refinement.

Slow Looking and Narrative Framing

In this appreciation exercise, participants spend extended time observing a piece, first recording only what they can objectively see. Interpretations and narratives are introduced later.

The distinction between observation and inference is assumed to strengthen critical discernment and bias awareness. By comparing different participants’ narratives, the exercise may also support perspective-taking and recognition of perceptual diversity, revealing how interpretation is shaped by prior assumptions and context.

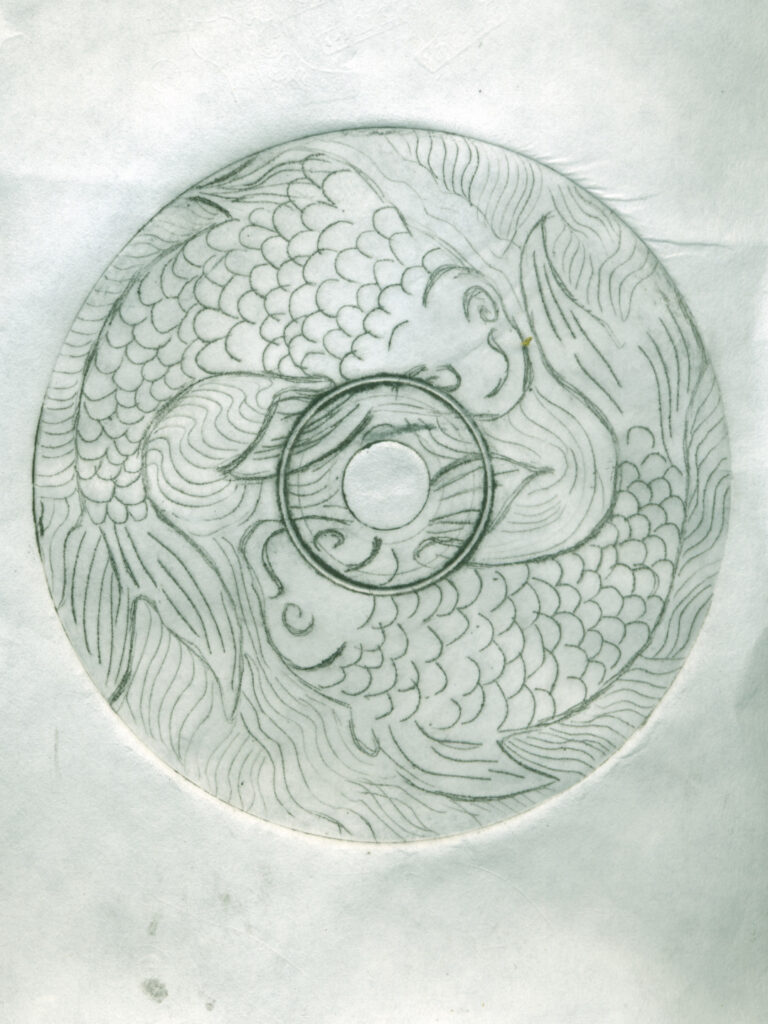

Drypoint Printmaking Using Recycled CDs

Participants are first shown how a drypoint print is made and are given access to a prepared plate to study. They can examine how the image sits within the scratched surface and how ink is held in the incised lines. They are then provided with a range of materials some or all of which may be useful during the process, and asked to work out how to prepare their own plate.

The shiny surface of the CD makes image transfer difficult. Participants must experiment: how can a design be transferred accurately? Some may discover that applying a thin layer of matt acrylic paint allows carbon paper marks to be discerned, making transfer far easier. Others may test alternative approaches.

This activity is assumed to strengthen problem solving under constraint, as participants navigate material resistance and incomplete instruction. It may also develop experimental thinking, hypothesis testing, and resourcefulness, as individuals test, fail, adjust and refine. The process foregrounds the relationship between observation, inference and practical adaptation, mirroring the way complex challenges often require material intelligence as much as conceptual clarity.

Layered Gelli Plate Collage Papers

Participants build layered papers through successive gelli plate prints, responding to what emerges rather than pre-planning a final image.

This process foregrounds emergent thinking, responding to evolving conditions rather than executing a fixed design. It may also cultivate ambiguity tolerance, adaptive iteration, and pattern recognition, as participants identify possibilities within partially formed layers.

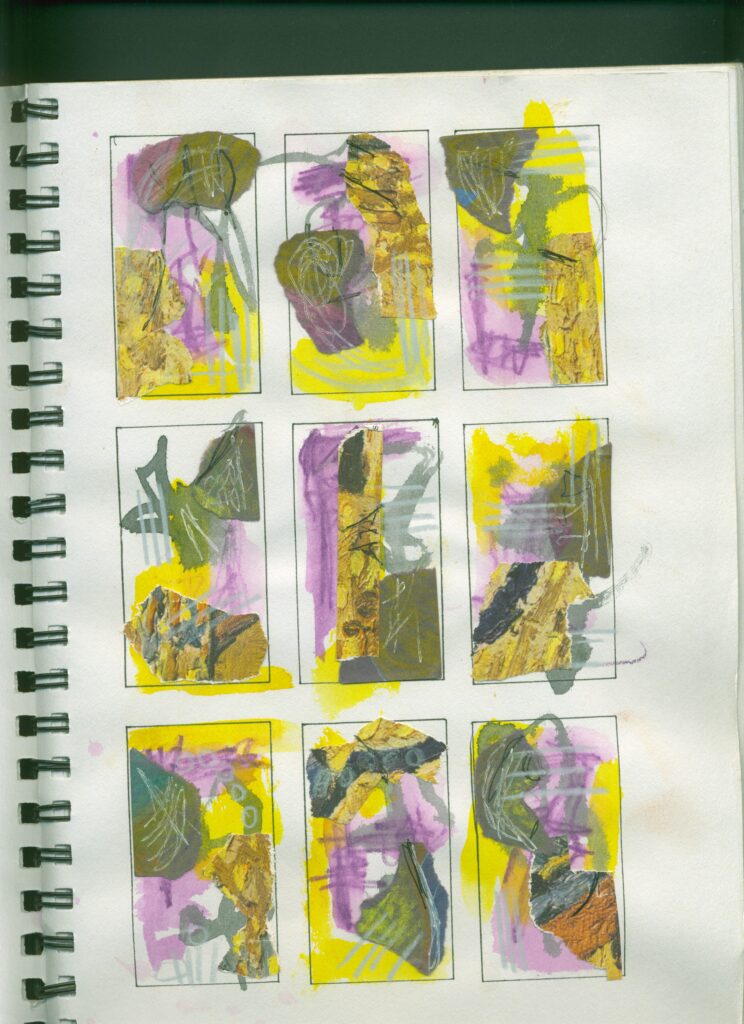

Grid Drawing and Repeated Mark-Making

Participants work within a grid structure, producing a series of small compositions using the same limited colour palette and collage materials. Through repeated mark-making, patterns begin to emerge — some intentional, others accidental. Small shifts in pressure, spacing or placement generate visible variation across the grid.

This activity is assumed to strengthen pattern recognition, as participants notice relationships across multiple iterations. Repetition supports attentional discipline and sensitivity to variation, training the eye to detect subtle differences rather than dramatic contrast. Working within a grid may also cultivate structural thinking, as each unit must function independently while contributing to the coherence of the whole.

After completing the grid, participants are invited to select “favourites” and justify their choices. This stage introduces evaluative judgement, requiring participants to articulate criteria rather than relying solely on instinct. The act of comparing pieces supports reflective analysis, prioritisation, and metacognition, becoming aware of why certain solutions feel stronger or more resolved.

By combining repetition with comparison and justification, the grid becomes not only a compositional device but a training ground for informed decision-making.

From Artistic Process to Thinking Capability

These activities do not assume that art automatically produces better thinking. Rather, they begin with a hypothesis: that artistic processes contain embedded cognitive disciplines. For example, composition trains prioritisation; layering models complexity; iteration normalises adaptation; slow looking reveals differences in perception.

The next stage of this work is to test these assumptions systematically. If artists do “see differently”, it may be because they practise forms of thinking that are structured, embodied and materially grounded. By making those practices explicit and participatory, it may be possible to strengthen thinking capability more widely.

- Do Artists See Differently? Art as a Training Ground for Thinking - 20th February 2026

- Do NOT Eat the Goblin Fruit – Train the Trainer - 27th January 2026

- AI snippets - 16th April 2018

Be the first to comment